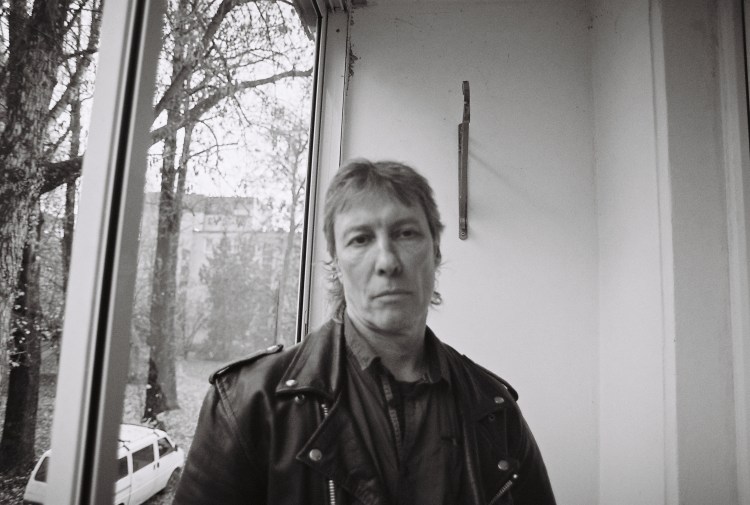

The Lithuanian heavy metal giants Katedra have been flashing across my musical radar for nearly half my life—probably since 2005, when I first saw them live at the “Roko naktys” festival. I screamed “Mes jėga” (“We are the force”) at the top of my lungs, banged my head, and danced with the crowd to their music. I never imagined that one day I’d be sitting in the kitchen of Katedra’s vocalist, guitarist, and founder Ričardas Laginauskas, drinking tea and listening to the story of this legendary Lithuanian metal band straight from the source.

For those who might have forgotten, Katedra was founded at the end of 1986 when guitarist Ričardas Laginauskas invited his childhood friends—bassist Algimantas Radavičius and drummer Marius Giedrys—to play heavy metal together. Soon after, former Foje guitarist Romas Rainys joined the group, along with then-little-known vocalist Povilas Meškėla.

The band found instant success, not just in Lithuania but also abroad. They were regularly invited to international festivals such as “Rock Panorama” (Moscow), “Rock Summer” and “Rock Winter” (Estonia), “Liepajas Dzintars ’88 and ’89” (Latvia), “Sopot” (Poland), “Ilosaari Pop” (Finland), “Baltic Sea Music Fest ’91” (Sweden), and the Lithuanian Culture Days in Leipzig ’94 (Germany). They continued their musical career for a full thirty-three years, right up until June 2019.

When Katedra stepped off the stage, they left behind a heavy metal vacuum in Lithuania. Their farewell went largely unnoticed in blogs or on social media. So it’s no surprise that my conversation with Ričardas began with questions about the band’s final performance at the “Kilkim žaibu” festival.

“Katedra” played their final show a little over six years ago—on June 23, 2019, at the “Kilkim žaibu” festival. There isn’t much information in the press or on social media about your decision to end the band. I imagine I’m not the only one curious—why and how did you decide to call it quits?

To tell you the truth, we’d played this festival before—back in 2012 we performed with Povilas Meškėla (Katedra Lead Duet). The 2019 show in Varniai was our last festival, but even before Kilkim žaibu we played our final concert at the “Lemmy” club in Kaunas.

Why did I decide to end Katedra’s journey right then? It might sound strange, but I had a feeling. Of course, I couldn’t have known the COVID pandemic was coming, but I just knew that a dead calm was approaching for live music. I felt it was time to stop and reorient. Even in 1986, I had a hunch there’d be a metal boom—I knew we needed to find a vocalist, a second guitarist, and the right stage outfits. And that’s exactly what happened—those were Katedra’s golden years. I went all-in, did whatever it took to reach my goals—and it paid off.

That same inner voice, intuition—whatever you want to call it—visited me again in 2019. I realized that trying to drag a dying band along would be a mistake. It would be better to end it entirely. I thought maybe someday I’d revive Katedra, or maybe start a solo project.

Actually, the “Velnio akmuo” festival invited us to reunite and play as all five original members. We declined—we couldn’t agree among ourselves. Not long ago, we were once again considering a Katedra comeback, but then I found out that “Velnio akmuo” won’t be happening anymore—they decided to end the festival after thirteen years.

Honestly, I probably wouldn’t even think about any additional Katedra shows if I didn’t occasionally get offers to perform again—even if many of those offers aren’t serious.

Does this mean fans should bury any hope of seeing Katedra on stage again?

I don’t know. I’ve still been considering a solo project. Katedra and the heavy metal style put me inside certain musical boundaries that I couldn’t step outside of. With a solo project, I could finally bring to life all those creative ideas that never made it into the band—I could return to hard rock or even stoner. I know stoner rock really well—it’s what I started with. Even before Black Sabbath broke out, there were some pretty solid stoner bands that Ozzy himself learned from. So I could play that kind of music. But I won’t do it just for the sake of doing it—I have to feel that the time is right, that I can do it and do it well.

There isn’t much written in the press about your life before forming Katedra. What’s the group’s origin story?

We started playing in school, at what was then the Seventh Secondary School in Žirmūnai, Vilnius. There were three of us. I liked that setup the best, because before that I was playing in a huge ensemble I’d barely managed to join as a bassist. But I didn’t want to play bass—I wanted to be a guitarist. I got lucky. I brought my own bassist into the ensemble, which let me switch to guitar. In that group, two girls sang ABBA songs, and our teacher made us play pop. Even then, I understood something important that our music teacher also saw: he could tell we were going to be rockers, so he deliberately made us play pop or anything but rock, and he made the other kids—who didn’t care—play rock. We were pissed, and that made our pop music more interesting. No wonder we started to rebel.

Now I teach myself, and I sometimes use the same tactic. Still, today’s youth aren’t inclined to rebel. They have everything—they’re full and don’t need to push back. We were hungry, and hunger brings results: you seize every opportunity, take everything with intensity. We were young, could go three nights without sleep, shout and scream, and still perform perfectly on stage. More than one professional vocalist told me that lack of sleep makes the subconscious more sensitive, helping you hear music differently—better.

So how did “Katedra’s” official activities take shape? And why did your paths diverge from R. Rainys and P. Meškėla?

We started Katedra’s career as a trio in 1986 (Algimantas, Marius, and I), but I was watching the most popular bands of the time and studying how they worked—for example, AC/DC played as a five-piece. They had three guitars: one lead, two rhythm, plus a dedicated vocalist with a separate vocal part. We couldn’t do that as a trio. I couldn’t split myself in half to play two very different guitar parts while also singing. So I started thinking about bringing in two more musicians. Iron Maiden, Judas Priest—they also had separate vocalists and multiple guitarists. That’s when I found guitarist Romas Rainys, but we still needed a vocalist.

Our drummer brought Povilas Meškėla to one rehearsal, and I immediately led him to a piano and asked him to show me his vocal range. When he started singing, “his lungs opened up,” and I realized he had something powerful. I remember during rehearsals, we’d put a huge bag over his head so his voice wouldn’t carry, and he’d just scream and sing at full strength underneath it—he was training his voice. On stage, he surprised all of us with his performance.

R. Rainys played with passion, and I played with aggression. Together we were a force. Still, R. Rainys and P. Meškėla started creating their own rock ’n’ roll project, and in 1991, we split up over personal disagreements. After P. Meškėla left, I couldn’t find another vocalist like him in all of Lithuania—one would miss the mark, another would scream too much—there was no golden middle ground. Eventually, Darius Mickus from Rebelheart advised me to sing myself. I listened to him, and from then on I handled vocals myself. I never found another guitarist like Romas either.

Second, our golden age—and not just ours, but for many similar bands—came to an end. The Soviet Union collapsed, Lithuania regained independence, and then came a kind of paralysis and stagnation.

I was always strict and kept a tight grip on the band because it was made up of strong personalities. Back then, it was almost expected for rockers and metalheads to be drunk, so I had to walk a fine line between the wild side typical of metal culture and absolute discipline. I was really strict, but for good reason—I truly believed in what I was doing. I could climb over anyone to achieve musical heights. And I did. Eventually, the tension became too much even for Marius Giedrys, and finally, Algimantas Radavičius also left the band.

I was born in independent Lithuania, so it’s hard for me to grasp what musicians went through during Soviet times. Did censorship really limit your activity?

It was hard, though we were somewhat lucky. After all the concert stuff and the “Roko maršai” tours, we were allowed to release a record! That’s when the real bureaucracy began—we had to go to what was then the Methodical Center, where we had to “defend” our songs.

There was a clever poet working there who would rewrite lyrics deemed “too folk-like” with his own versions and get paid royalties for it. But I saw a disconnect in his revisions—he didn’t grasp the themes of the times. I mean, how could a respected poet understand punk ideas and write lyrics for them? Katedra’s lyrics were different—spirits, horror film themes. Somehow, I managed to slip past the censors—I found common ground with the guy at the center. Sometimes we negotiated, sometimes we co-wrote. I’d warn him which lines I was going to change, and in other cases, I let him rewrite them as he liked.

Eventually, I met the late poet T. A. Rudokas, who I think was a truly great professional. He helped revise the lyrics for Mors Ultima Ratio, because, in his words, I “lacked poetic devices.”

You’ve mentioned that musical mastery has always been important to you and that you deliberately sought out top-level musicians. But it’s no secret that “Katedra” also paid attention to stage image—leather, spikes, teased hair. What was more important to you—music or theatricality?

Music was always more important. During our early concerts in the Soviet era, it was difficult to even get leather. We had to pay a lot of money just to obtain it. We went through half the factories in Vilnius trying to get spikes made. All five of us worked hard to look the part of a metal band. Still, we didn’t all wear the same outfits—we somehow divided it up: who would wear bracelets, who wouldn’t. Later, all of us dressed up.

A few years later, everyone was dressing like that, and I got bored. That’s when thrash metal started to spread, and I liked it even more than heavy metal because thrash had tougher guitarists. That was around 1990, and differences started to appear between us. Romas Rainys had come to Katedra from Foje. He was different—deeper, calmer. My speed metal arpeggios weren’t really his thing. It became clear he felt pressured.

I remember at the “Sopot” festival in Poland, in the summer of 1991, five German music managers were watching us. After the show, one of them came up and asked if we had just played old songs. He said he expected Katedra to be thrash metal with a different, growling vocal style. Povilas refused to growl—he didn’t want to damage his voice. As you know, we later parted ways, and I never found a better vocalist. Life eventually forced me to sing myself.

Once the band was down to just three of us, I had to shoulder both guitar and vocal parts. I had to rethink the second album, Natus in Articulo Mortis, myself. Some critics say it’s even better than the first, Mors Ultima Ratio. The second album is definitely angrier. Our managers convinced me to sing in English, though I sang better in Lithuanian. The translation was done just the day before recording, and the studio was under renovation at the time. There was a lot of background noise—it was hard to focus.

Playing as a trio meant not only making a good recording, but also arranging the music in a way that the listener wouldn’t notice any gaps during live performances. With fewer guitars, less accompaniment, certain empty spaces would appear, and I had to rethink and compromise. That’s another reason why musical skill has always been so important to me.

“Katedra” had a creative pause between 1994 and 1999. What was happening in your lives during that time?

In 1994, we played a concert in Leipzig, Germany. Before that, we’d constantly been rehearsing, working creatively in the “Kino studija” (Film Studio) in Antakalnis, where we had about 200 square meters of space. But for about two years leading up to that Leipzig show, we no longer had a place to rehearse—we were bouncing from one place to another because we could no longer use the Film Studio.

We stopped performing abroad, and our income dropped. At the same time, Lithuania was going through an economic downturn, so we had to pause our musical activities. Marius cut his hair and started working at customs. They offered me and Algis jobs there too, but we refused—we didn’t want to rummage through people’s handbags or cut our hair, which at the time reached our chests. On top of that, I was spending part of my time in Sweden, so we drifted apart.

The musical pause eventually ended. After 1999, you released two more albums—III (2006) and Ugnikalnis (2008). What made you continue your journey with “Katedra”?

From time to time, we still rehearsed and eventually decided it was time to regroup. I started auditioning vocalists again. At one point, Ąžuolas Stanevičius from the AC/DC project played with us for a while. There were a lot of experiments. We even flirted with industrial metal—something close to Rammstein. Eventually, we reformed, but we were different than before—more mature.

At the same time, music trends were shifting. Jazz-rock became popular, and concerts moved into bars and music clubs. Everyone wanted to play at “Brodvėjus.” Club managers would ask me to perform covers of MTV hits. I didn’t play covers, but I had to earn a living somehow. We saw that our music was too heavy for those bar settings. That might be why our third album, III, is much lighter than the first two—maybe even too light.

With the fourth album, Ugnikalnis, I tried to shift direction and make the music heavier again, but by that time we were already disconnected from the public. I didn’t know what people were listening to anymore. In 1986, when I was in my twenties, I was closer to people—I spent more time with them, talked, hung out. Later, everyone split into their own groups.

Eventually, with both Marius and Algis no longer in the band, the dynamic changed, and so did the connection with the new musicians. With Marius and Algis, we could play for hours on end—there was this creative chemistry in the air. We couldn’t replicate that later, even though we played with incredibly talented and professional musicians. I even tried playing with my son (he’s a drummer), but still, that connection wasn’t there.

What was the secret to “Katedra’s” success and popularity?

I was always uncompromising, unwilling to conform—I went after what I believed in with full conviction. That paid off. Just think: most of society looks at rockers and metalheads as marginal figures whose music is listened to by maybe 2% of the youth. And here comes a metal band that elbows its way into the spotlight alongside pop stars and won’t let them pass. I’m talking about Antis, Bix—we were strong competition for them, never compromising musically. What metal band today competes with pop giants?

I never sacrificed music just to please an audience—I always allowed myself to do what I wanted. I would’ve performed even for five people. But back in the ’90s, we were being invited to play at the Vilnius Sports Palace, and the audience filled the venue. At one Lituanika festival, there were around 12,000 people.

In fact, we saw even bigger crowds at foreign festivals. Lithuanian rock festivals were also packed. It was a great feeling, though we didn’t appreciate it at the time—we thought it would always be like that. By the end of 1994, the wave had passed. Only about 300 people showed up at the Sports Palace—it felt empty. But this decline coincided with stagnation in Lithuania, so audience numbers dropped across the board.

One alternative that might have drawn bigger crowds was stage theatrics and show elements. But I didn’t want that—I didn’t want to put on performances like Rammstein. I wanted to perform music. That’s why I chose the thrash metal path—no extravagant costumes, no pomp, no spikes. Still, after Marius and Algis left, I realized I would need to simplify the music—not refine it—to make it easier to perform.

Did you ever consider re-releasing your first two albums, “Mors Ultima Ratio” and “Natus in Articulo Mortis”? I’m sure there would be immediate interest, both in Lithuania and abroad.

We’ve been offered that so many times! Many managers have approached me… But I was never really interested in the records themselves or in their release. I always focused on the music: how to record it, how it would sound, how to arrange it in the studio. Once a record came out—that was it. I lost interest. No re-releases, no reissues. Besides, the sound quality of both albums is very poor—there’s nothing to salvage. It would be easier to re-record them—but we wouldn’t play like we did in the ’90s anymore. The heart just isn’t in it. Better to leave them as they are.

“Katedra” members didn’t just play music—they also appeared in film, such as the German horror movie “Rats II”. What’s the story behind that?

It was all pretty simple. We rehearsed at the “Kino studija,” where film shoots were always happening. Sometimes we got involved in those projects. We even beat the drum for the TV series Robinzonas, and we appeared in Rats II, where we played a wedding band. The best part was that the shoot took place at Trakai Castle. I even played in some animated film once, though I can’t remember the title. We made brief appearances in several Lithuanian films that now just sit forgotten on shelves.

By the way, director Algimantas Mikutėnas is a good friend of mine—he filmed Katedra’s music videos for “Žvaigždelė” and “Kalinys.” You’ll notice the videos are barely edited—that was his artistic intention, to film clips without cutting.

“Kino studija” was a hub for creative people, which is why we participated in so many projects there. Unfortunately, in 1991, we were kicked out for bad behavior. Around the same time, R. Rainys and P. Meškėla left the band. After a long break, we returned to the Film Studio in 1996 and rehearsed there for another ten years. After that, we moved to the Officer’s Club, but it was no longer the same creative environment. Things worked out for us while we were at the Film Studio.

In your opinion, what part of your music was the most unfairly overlooked?

I think our fourth album. Ugnikalnis was a compromise that combined everything in our creative output. I really like its quality, but it didn’t get the recognition it deserved.

The second album, Natus in Articulo Mortis, was also undervalued—maybe it would’ve been different if the recording quality were better. At the time we recorded it, the studio was experimenting with new equipment. There was a new mixing board, a new tape machine—we really struggled through that session. It felt like a lab experiment. We should have stopped, come back later, and fixed or redone things—but we didn’t. That’s probably why I was so strict when recording the third and fourth albums—everything had to be done in a single take.

So it’s no surprise that we recorded the third album, III, in about an hour at “Tamsta.” After the session, I said that if anything needed fixing, I’d come back and record the guitar again later. Sure, there were things to correct, but at least we didn’t suffer through the process.

And which song is your personal favorite?

From the first album, it’s “Dvasių šėlsmas” (“Dance of the Spirits”). Also “Prarastas rojus” (“Lost Paradise”)—a song the public totally overlooked. Honestly, all the songs are like my children—I love them all, they’re all dear to me.

In “Dvasių šėlsmas,” I managed to solve certain harmonic composition challenges—transitioning smoothly from one key to another without breaking any rules, even masterfully. Now I might do it differently, but at the time, that was a major win for me, which is why I love that song. Right after Lithuania’s independence, it was high up in the charts for a long time. At one point, we nearly filled the entire M-1 Top 10—it was basically all Katedra songs.

We even received recognition from foreign critics: in 1989, the cult magazine Metal Hammer published an article about us. It said we were more technically skilled and musically advanced than 90% of Western European bands. A German journalist I was in contact with at the time predicted we wouldn’t last long because we were still behind the Iron Curtain—but he was wrong. Katedra ended its run twenty years after that interview.